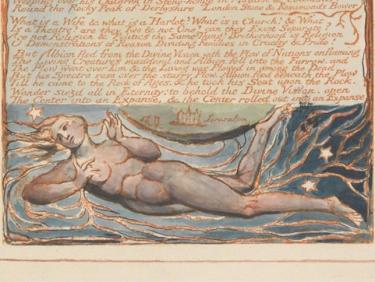

William Blake: Untitled (Jerusalem) (1810)

On how ideas become words, and words become music. How they are mutable, shape, and are shaped, by peoples and nations.

Few things speak to both the tensions and absurdities at the heart of England’s oft-fraught search for a sense of national belonging – an English Heimat – so well as the poem that takes its name from a Middle Eastern metropolis, ‘Jerusalem’. It resounds with equal conviction from the beer-soaked terraces of national cricket and rugby matches, as it does from parish churches; as much at home during the flag-waving jingoism of the Last Night of the Proms, as following The Red Flag at the Labour Party conference. Yet, despite so emotively permeating such diverse aspects of national life, its words are notoriously ambiguous, and their interpretation has long been a battleground for competing visions of an English Heimat itself.

Till we have built Jerusalem

The poem appears, untitled, in the preface to Milton, a sprawling and prophetic book by William Blake (d. 1827). Quite unlike its modern performance, the text is remarkable for its doubt and uncertainty, asking the listener a series of earnest questions: did “those feet” and “the holy Lamb of God”, visit England’s mountains and pastures? Did “the countenance divine” grant it special favour? Was a new Jerusalem built among the “dark satanic mills” of Industrial England?

Blake knew the answer to these questions was, no. Yet, he was also aware that from the 12th century, the Benedictine monks of Glastonbury Abbey had manufactured a sacred past through the figure of Joseph of Arimathea, a merchant who had donated his tomb to Christ. Possessed of the Holy Grail, he supposedly set out from Jerusalem to England. On his arrival, he was thrown into prison only to be saved by God’s intervention. Thereupon, Jesus sent the angel Gabriel to command him to construct a chapel at Glastonbury.

Such legends allowed Glastonbury’s monks to link their monastic Heimat to the life of Christ and the tomb of the Holy Sepulchre, and thus to Jerusalem itself. Yet, at a time of waning Latin-Christian rule in the Holy Land, this connection – as Blake was well aware – was also invested with transcendental ideas of Heimat: the Revelation of St John had emphasised how Jerusalem was not merely the physical site of the Resurrection, but rather a representation of a new Heimat – a heavenly new Jerusalem bequeathed by God.

If the monks had hoped this could be built at Glastonbury, then such visions – along with the pilgrim revenues brought by Joseph’s relics – were swept away by the Reformation. In this new Protestant Heimat, Blake offered a radical alternative: he called for “mental fight” against “church and king”, and would have been astonished at the connotation his words would have after Hubert Parry’s musical arrangement for the nationalistic Fight for Right Movement in 1916. Yet, he would perhaps have been less surprised at its enduring ability to subvert established institutions. In a 1969 Monty Python sketch, Eric Idle sings “And did those teeth...” while being fondled by Katya Wyeth, only to be abruptly censored by Graham Chapman’s establishment colonel - an ironic foreshadowing of real events. In 1973, Emerson, Lake & Palmer’s rock cover was banned by the BBC. A fate that did not befall Fat Les’ football anthem or the Pet Shop Boys’ disco reworking, but they may have contributed to Southwark Cathedral’s decision to ban the song in 2012 as it is “not to the glory of God”.

Which Jerusalem?

It remains the soundtrack of national events – Edward Elgar’s arrangement is played at royal ceremonies, most recently at the funeral of Prince Philip. Yet, as England is reshaped by globalisation, it continues to be reinterpreted in strikingly different ways. In 2008, it evoked a multicultural present in an arrangement for sitar in the film Dean Spanley; in 2010, Jez Butterworth’s play Jerusalem contrasted a sacral past with a gentrified and sanitised modernity; and, following the Brexit referendum of 2016, it has been used by both sides to articulate a future vision.

Blake’s lyrics retain their power to communicate profoundly different visions of Heimat. Grieving the human and cultural costs of war, Parry came to regret their reworking and granted his copyright to the suffragettes in defiance of imperialistic appropriation. Herein, he was perhaps aware that, like Jerusalem itself, they have long straddled tensions between progressive and conservative ideals, exposing an ongoing contest over what England was, what it is, and what it should become.

Heidelberg, May 2025

John Aspinwall, TP A04